Tea-Tokens: A forgotten chapter in the history of tea plantations

The emergence of tea as a beverage in India is a unique social event in history. Sylhet, Assam, Cachar, Dooars, and Darjeeling were preferred for tea production, considering the hill climate favorable for tea production. These tea regions were known as Surma, Assam, Barak, and Brahmaputra valleys. Tea production began in the middle of the 19th century. At that time, it was unprofitable for the plantation authorities to pay the wages of the workers in the government currency. That's why workers were given tea-tokens as wages.

This facilitated the payment of daily, weekly, or monthly wages to a large group of workers. These not only reduced the hassle of storing large amounts of petty cash but also reduced the financial burden on tea planters. There were tokens of different values, pi, paisa, anna, and then. They were of all shapes and sizes; such as round, oval, triangular, hexagonal, and octagonal.

The value of the tokens was fixed in relation to the wage rate of the workers. The use of tokens was limited within the geographical boundaries of the garden. As everyone concerned with the garden was well aware of their value, no problem would have arisen. For almost a hundred years, these tokens have played an important role in the lives of tea workers.

Basically, the stories and accounts of the discovery of these tokens are known from the journals related to currency. Why and how the tea-token based system was developed in tea plantations despite the existence of the monetary system in British India is discussed in the article.

Pre-colonial and colonial era currency and banking

In 1742, the British initiated the minting of 'Arcot' coins at the 'Arcot Mint,' having secured permission from the Mughals. According to historian Abdul Karim, there were over two hundred mints operating across the subcontinent during that era. However, it is noteworthy that the coins produced by these mints varied in weight. The valuation of coins depended on their weight and the quality of the metal used.

Coins served as the medium for government revenue collection, and business transactions predominantly transpired using Arcot coins. Entrepreneurs such as Shroffs, Seths, and Poddars in Dhaka thrived by employing currency exchange techniques. Collecting coins from various sources, ranging from common individuals to zamindars and the East India Company, was necessary to meet revenue obligations. Consequently, disparities in the "batta" (a premium or fine imposed on non-standard rupees circulating in the market) were assessed in conjunction with fluctuations in the value of currency denominations.

In response to such financial difficulties, the Union Bank was established in 1828. However, it ceased operations in 1848. Dhaka Bank came into existence in 1846 but suspended its activities in 1856. In 1862, the directors of the 'Bank of Bengal,' operating within the Presidency Division comprising six West Bengal districts, acquired Dhaka Bank. Nevertheless, the Bank of Bengal's impact on the investment activities of the Poddars remained limited because both ordinary people and the wealthy segment of society were hesitant to deposit their funds in banks.

Furthermore, obtaining loans from Poddars was a relatively straightforward process, further discouraging trust in banks. Dr. RM Debnath's records indicate that between 1913 and 1917, 78 banks shuttered in undivided India, followed by the closure of 373 banks between 1922 and 1932, and another 620 banks between 1937 and 1948. These statistics underscore the lack of a robust foundation in the banking system during the first half of the 20th century.

The monetary system in Sylhet presented a distinct scenario. In 1778, Robert Lindsay assumed the role of 'Resident' in Sylhet and documented that the region had a dearth of silver and copper coinage during that period. Instead, revenue payments were made using kori. The calculation rules for kori at that time were as follows: 4 kori equaled 1 ganda, 05 ganda equaled 1 bori, 04 bori equaled 1 pan, 4 pan equaled 1 anna, 4 annas equaled 1 kahn, and 10 kahn equaled 1 taka.

By 1820, the use of these koris as currency ceased. The currency system in the Assam province closely resembled that of Dhaka, featuring British coins, Narayani coins, Arcot, Sikka, and Raja-Mohri. The exchange rates for this diverse array of currency varied.

Pre-colonial and colonial communication systems

In the pre-railway period, the best means of communication in Bengal was the river route. Apart from this, cow and buffalo carts and elephants were used for transportation. In many cases the condition of the roads was such that it was quite difficult even to walk there. It is known from the book 'History of Eastern Bengal Railway 1862-1947' written by Dinak Sohani Kabir, that time it took about 13 days to reach Kolkata from Sylhet.

The communication situation in Assam and Sylhet was more fragile than in Darjeeling. Because in 1878 railway communication was established till the foothills of Darjeeling. On the other hand, the Assam-Bengal railway was fully operational in 1904. And railway connection with Chittagong port was established in 1910. According to 1916 records, it took eight days to reach Silchar by steamer from Calcutta Armenian Street Ghat.

Steamers from Calcutta Jagannath Ghat reached Dhubri in seven days, Guwahati in nine days and Dibrugarh in thirteen days. Many places, including narrow canals, had no steamers. The rest of the way had to be crossed in native boats.

Risks and costs of transporting metallic coins

Transporting currency by boat was quite risky. The 1847 accident serves as a testament to this watershed moment. The boat capsized while transporting Nazrana coins given by the East India Company to Koch Raja down the Gadadhar River to Dhubri. All the coins sank into the water. To mitigate such situations, later coins were placed in numerous small bags, with each bag tied to a floating bamboo raft. This approach ensured that even in the event of a boat accident, the bags tied to the raft could be recovered, enhancing the security of currency transactions.

Mint authorities implemented more robust currency management practices, especially for transporting small denomination coins, which were transported in large wooden crates. These crates contained stacked packets of coins that were securely packed, sealed, and cross-tied with special wire, bearing mint marks.

The multidimensional tea-token and its use

The "pai" served as the smallest unit of currency used in British India after the monetary system stabilized. Above the "pai" were the "money," then the "anna," and finally the "rupee," with 192 "pies" or 64 paise to one rupee. One anna was equivalent to 12 pies, and 16 annas made up one rupee. To pay the wages of workers, a significant number of small denomination coins such as "pies," "paisas," and "annas" were required.

However, due to a shortage of these coins from the mint, the authorities of tea estates faced considerable challenges and had to go to great lengths to mint large quantities of money to obtain the necessary coins. To address this crisis, many tea estate authorities began using tea-tokens as their medium of exchange.

These tokens were made from brass, zinc, copper, and tin. In addition to metal tea-tokens, there were traces of colored cardboard eight-anna value tokens (of Assam Company). Some tokens had a face value, while others were based on work rates, such as the Quarter Hazri type tea-tokens. The term "Hazri" used in the tokens originated from "Hazira." "Day attendance" was the method of remuneration in those days, with a specific type of work assigned for "Dayhajira," meant to be completed within one day. There was a fixed rate of daily remuneration for this work. The wage system for tea plantation workers differed from that of other industries or agriculture, as jobs were allocated to families rather than individuals, with husbands, wives, and minor children all contracted to work. "Tikka," or extra work, was compensated at a slightly higher rate.

According to coin collector and expert Shankarkumar Bose, several hundred tea-tokens have been identified from a total of 85 tea plantations in Assam, Barak, and Brahmaputra valleys, including 54 in the undivided Surma (Sylhet) valley. These tokens typically measured twenty to thirty-two millimeters in width and predominantly featured English characters. Some tokens also bore inscriptions in Assamese or even Bengali, such as "Chilet." While some tokens had writing on only one side, most had inscriptions on both sides. Notably, none of these tokens displayed denominations; they solely featured the name of the tea garden. Presumably, to avoid the attention of the Labor Inquiry Commission, many tea estates refrained from indicating monetary values on their tokens. Furthermore, many tokens were engraved with the year of issue, and most of them featured round holes in the center. Three different shapes of tokens were used for male, female, and child laborers, with the remuneration rates being highest for adult male workers.

Tea-tokens were primarily supplied by managing agents, who acted as intermediaries between the mint and the plantations. These agents assumed responsibilities ranging from placing coin orders to supplying tokens and even lending money to the tea garden authorities, similar to a bank. A 3 percent commission rate was customary for their services.

They functioned as lenders to the tea garden authorities, essentially serving as a financial institution. Octavius Steel & Co. became famous as a prominent managing agent in the Sylhet region, overseeing a total of 28 gardens. This firm operated as a subsidiary of Duncan Brothers, who themselves possessed their own tea garden. In accordance with government directives, both Calcutta Mint and Birmingham Mint were responsible for issuing tea-tokens in response to the demands of the tea estates. Originally a privately-owned mint, Birmingham Mint underwent a name change to 'R. Heaton & Sons.'

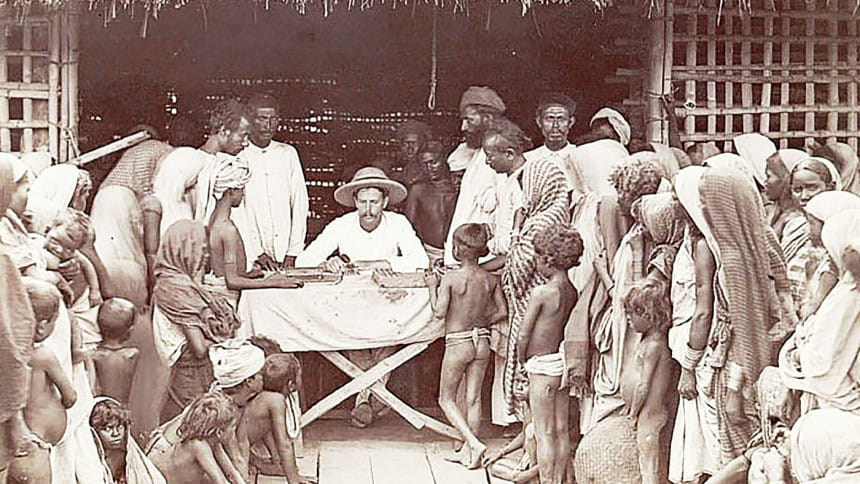

Each garden had its own moneylender's shop, where workers could purchase daily necessities with tokens. Agents employed by the garden authorities would collect tokens from the moneylenders weekly, paying the exchange rate. The task of remunerating laborers with these tokens was generally carried out by sardars, who oversaw the laborers directly. Sometimes, European gardeners would also disburse workers' wages, which were typically paid on a daily basis in most plantations. Tokens were distributed early in the morning for the previous day's wages.

The token system in tea gardens served another underlying purpose. Due to the strenuous work, harsh environment, and exceedingly low wages, workers often sought to escape the plantations. However, there was no means of escape, even if they wished to visit their relatives, as these tokens held no exchange value outside the garden. Consequently, workers could not leave the garden, even if they desired to.

As per Nasim Anwar, the initial metal tea-token made its debut in 1870, and the final token request was made in 1930. This token system endured until the 1950s. Following the partition of the country, the tea-token system came to an end as currency became widely circulated. Nevertheless, these tea-tokens continued to bear witness to the joys, sorrows, and aspirations of the tea workers.

Hossain Mohammad Zaki is a researcher.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments