Re-discovering the goddess in medieval bengali poetry

The Medieval period in Bengal was noteworthy for its amazing religious syncretism, with the fusion of Shaiva, Shakta, and Vaishnava cults with regional folk traditions. It also witnessed the blending of Hinduism with the Buddhist Mahayana and Vajrayana sects, as well as with Islamic culture. In verse forms like the 'panchalis' and 'padavalis,' we find the amalgamation of Brahminical rituals with women's vratakathas, Puranic myths with pre-Aryan legends, and oral and visual art forms with the literary.

The Goddess figures in medieval Bengali poetry take on interchangeable roles with their human counterparts. The goddesses are both divine, inscrutable, and powerful on one hand, and exquisitely human, vulnerable, and victimized on the other. These dual aspects are expressed through the humanized voices of Chandi and Manasa in the Mangal Kavyas, and that of Radha in the Vaishnava padavalis. We also hear the voices of Sita, Kausalya, and even Kaikeyi in Krittivasa's Ramayana, each echoing the cries of exploited women.

These cries of suffering women are further exemplified in the fusion of Sita's 'baromasi' with the authorial voice of Chandraboti in her sixteenth-century Ramayana. The texts reveal the woeful experiences of women in a staunchly patriarchal society, giving rise to beautiful images of courage, dignity, and quiet power.

The images of the goddess in her many voices can be juxtaposed against those found in canonical Sanskrit texts as well: those of Chandi in the two stories of Mukundaram Chakroborty's Chandi Mangal vis-a vis those of the Devi in the Devi Mahatmya and the Devi Bhagvata Purana, of Manasa in the story of Behula-Lakhinder against that of the Adya Shakti with whom this regional folk goddess eventually blends, of Kali in the Kalika Purana against those in the tantric texts, of Sita in Krittivasa's panchalis and Chandraboti's 'baromasi' against that in the Ramayana of Valmiki.

The Medieval period in Bengal was long and turbulent. This was reflected in a chronicle of foreign invasions, conquests, internecine struggles between dynasties, and conflicts among warring feudal lords. Consequently, the socio-political scene was fraught with uncertainty. Religious conversions, the destruction of religious shrines, and the influence of various religious traditions necessitated a reinforcement of the waning faith among a confused populace. The common people needed to reconnect with the religion of their forefathers in a manner that was comprehensible to them, achieved through myths and storytelling, rather than through Brahminical liturgical texts or Vedic rituals.

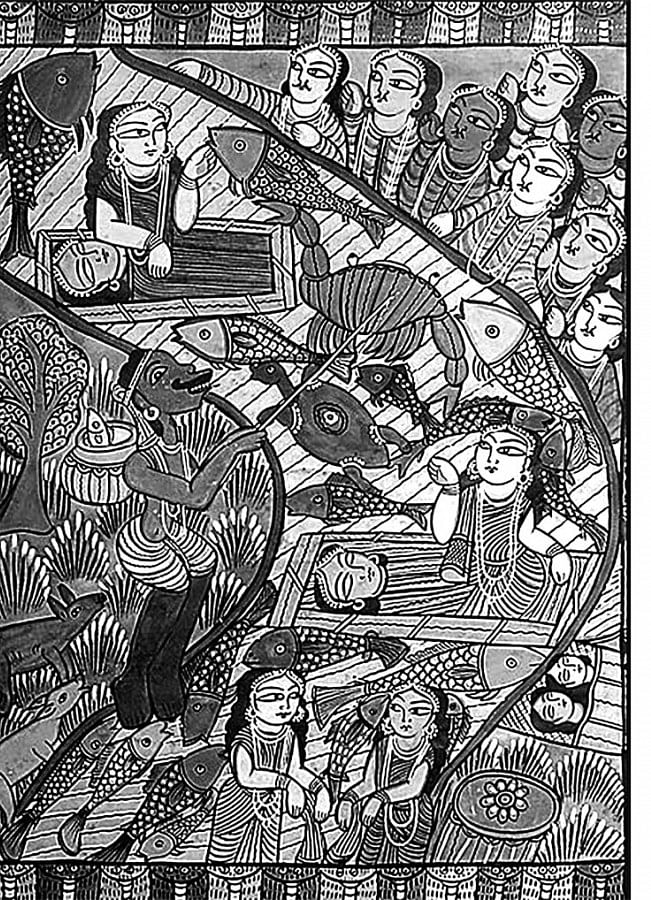

In the Mangal Kavyas composed between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries, the goddess is seen as attempting to re-assert herself in a patriarchal society and an andro-centric religious order. The story-line of each of these Kavyas is that of a powerful man like Chand or Dhanapati Saudagar who is firmly committed to the worship of a male deity, being converted to goddess worship with the chastening words:

'Sravan Mangal-katha Debir pujar gatha

Shunile bipad pratikar

Eyee vrata itihas shunile kalush-nash

Kali-juge hoilo prachar.'

(Chandi Mangal, Mukundaram Chakroborty)

In the Mangal Kavyas, whether it is Chandi or Manasa, the Goddess figure is depicted as fiercely malevolent and destructive to her dissenters on the one hand and benevolent and motherly to the faithful on the other. She is envisioned as a powerful warrior and devoted consort, often enduring indignities herself. She rescues her female worshippers who are victims entrapped and exploited by the politics of a marital home. In the Kalika Purana, on the other hand, Kali appears as a rebel, dominant in marital and sexual relationships, and ferocious and bloodthirsty on the battlefield.

Jayadeva's Gita Govinda and the padavalis of the Vaishnava poets Chandidas, Vidyapati, and Gobindodas show the emergence of Krishna, the flute-playing cowherd-lover of Radha and the gopis, from the Vedic god Vishnu. They express the pain and suffering of Radha's exquisite longing for Krishna. Radha is envisioned as a social rebel who defies the social constructs of 'sattitwa' and 'pativratya' imposed upon married women in a patriarchal society, as well as the compulsions of a marital home, the 'kul maryada,' to obey the call of Krishna's flute:

'Ke na banshi baye Bodai Kalini nadi-kule

Ken a banshi baye Bodai e goth Gokule

Akul shorir mor beyakul mon

Banshir shobode mo aulailo bandhan.'

The hagiographies talk about the cult of the Gaudiya Vaishnavas and Chaitanya's 'raganuga bhakti sadhana.' Chaitanya's arrival marked a liberation from doctrinaire rigidity and the spread of worship among the masses through the singing of 'keertans' dedicated to the Lord and the enactment of plays based on various myths associated with Him. Therefore, the Chaitanya Mangals of Bijoy Gupta and Lochanadas delve into the androgynous aspects of Chaitanya's relationships with his Lord and disciples. On one hand, Chaitanya is overcome by Radha-bhava in his worship of the Lord:

'Radhikar bhava-murti prabhur antar

Sheyi bhave sukha-dukkha uthe nirantar.'

(Chaitanya-Charitamrta, Krishnadas Kaviraj)

On the other hand, he is Krishna to his followers, as the love-lorn village-belles of Nabadwip overcome by desire confess:

'Kemon kemon kore pran uchatan….

Madan aloshye puri mon.'

This is similar to the plight of Radha described by the padavali poets.

The regional adaptations of the Ramayana story are an attempt to popularize the epic in the local language for the masses. By inserting local customs and traditions into the main body of the epic, the adaptations aim to create a scenario familiar to the readers.

Hence, Krittivasa wrote his epic in the form of the 'panchali,' which was popularly used by Medieval poets of Bengal, employing the 'payar' and 'tripadi' meters. Chastity for a woman is a double-edged weapon, as shown in this text. On one hand, it is a source of spiritual strength through strict observance of these codes. On the other hand, in a male-dominated society, it can become an instrument of subjugation. However, it also empowers virtuous women against rapacious males. A single blade of grass stands between Sita and the mighty Ravana, her captor, and he is powerless to cross the boundary set by her. Even noble and glorious epic heroes like Rama are not immune to the wrath of a 'sati-pativrata.'

A parallel vision of an empowered female is seen in Mandodari's curse of Rama after the destruction of Lanka and the demon dynasty in the epic war:

'Ami jodi shoti hoi bharot bhitore

Kandibe Sitar hetu ke khandite pare.'

And it is this 'sattitwa' of Sita's that Rama repeatedly calls into question in the public domain due to her prolonged captivity in Lanka, even though he is well aware that she is Lakshmi incarnate. It leads to the murmur of dissenting voices within the palace itself:

'Ki hetu parikkha nite chaho aar baar

Sitare janiyo tini Kamala aponi

Nahik Sitar paap jaane shorbo prani.'

In a final act of proud assertion of her inviolable chastity, Sita prays to her Earth mother to receive her and descends into the bowels of the earth, leaving Rama powerless to prevent or protest this act of defiance by a wronged wife.

Across India, women mourn Sita's sufferings and, through her, their own ill treatment at the hands of men in a patriarchal society. This is part of a rich oral tradition of alternative Ramayanas that give the silenced subaltern a voice. Here, the hero's dominance in the literary epics is replaced by the voice of the wronged woman.

These women's songs and 'Rama-kathas' are sung and chanted in exclusively female company within the privacy of homes or during such festive occasions as marriage or pre-birth rituals. In one Bengali song, as Sita is sent into forest exile, the poor innocent woman repeatedly looks over her shoulder and even blames Rama for her woes:

'Kicchhu kicchhu jaye re Sita

Picchhu picchhu chaye

Tobu to Ram er puri dekhite je paye..'

And she even calls her husband sinful.

The genre of the 'baromasi' is part of this tradition of women lamenting their woes in their marital homes, where a woman links each of the twelve months of the year with one aspect of her litany of sorrow. The sixteenth century poet Chandraboti uses this device to narrate Sita's tale of suffering:

'Sitar baromasi katha go dukkher bharoti

Baromaser dukkher katha go bhane Chandraboti.'

(In 'Mymensingha Geetika', Dinesh Chandra Sen (ed))

Chandraboti alternates between Sita's voice and her own authorial one in her ballad, crafting a tale of three wronged women. Mandodari, who takes poison in grief at her husband Ravana's debauchery, ends up becoming pregnant and delivers a golden egg, which she floats in the river water. A poor fisherwoman finds the egg and nurtures it until it hatches, then nobly offers the child to King Janaka to rear. Sita herself narrates her sad tale of abandonment.

The true villain of the epic is not Ravana but Kukuya, Sita's evil and jealous sister-in-law. It is she who fills Rama's mind with suspicion against his beautiful wife, not Rama's subjects as in the traditional version. This leads to Sita's abandonment, and Chandraboti introduces the theme of the complex politics of the marital home. The text concludes with the poet's prophetic voice, passing stern judgment against this unjust action that will lead to the downfall of the epic hero and the dynasty:

'Je agun jalailo aaj go Kukuya nanadini

Shey agune pudibe Sita go shohit Raghumani

Pudibe Ayodhyapuri go kichudin pore

Lakshmi shunya hoiya rajya go jabe charkhare.'

The Medieval period in Bengal thus produced some of the finest literature that we have ever known. Rich in variety, in spontaneity and in the synthesis of oral traditions and literary texts, it offered a form of religious syncretism even in the propagation of its cultic faiths that may serve as a noble example for future generations.

Saumitra Chakravarty teaches English Literature in the Postgraduate programme, National College, Bangalore, India.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments