Marina Tabassum: An architect in search of roots

The narrow “main” roads filled with potholes and iron rods plunging out, the scorching afternoon heat and a destination unknown to both google maps and a large section of people living in Faidabad in Uttara; these were the obstacles that my colleague and I had to overcome while in search of the Bait-ur-Rouf Mosque.

Designed by Marina Tabassum, a veteran in the field of Bangladesh's architecture scene, and completed in 2012, the mosque gained plenty of recognition in the last few months after it had been nominated for the prestigious Aga Khan Award for Architecture earlier this year.

The award is given every three years to projects that set new standards of excellence in architecture, planning practices, historic preservation and landscape architecture. Nineteen structures from all over the world were shortlisted this year from 348 nominated projects and the Bait-ur-Rouf Mosque is one of them.

And so, despite the roadblocks, there was plenty of enthusiasm -- almost akin to the excitement that two budding architects would have probably felt. After a rather rickety, one-hour ride, we reached our destination.

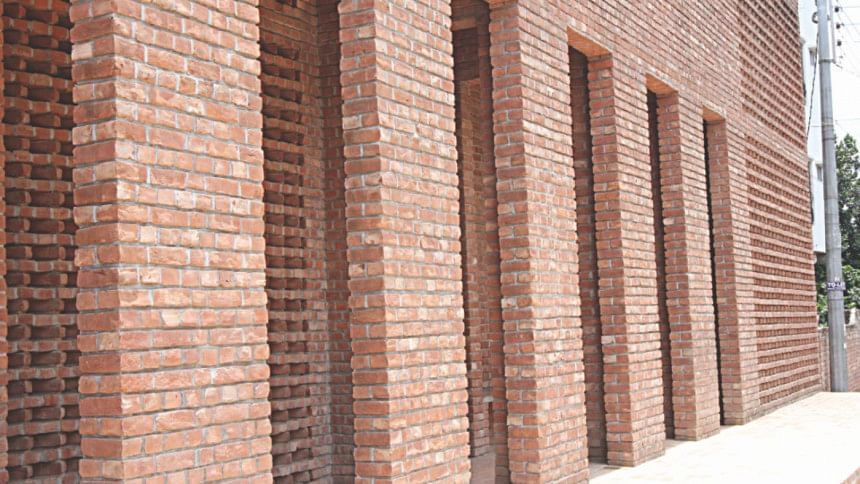

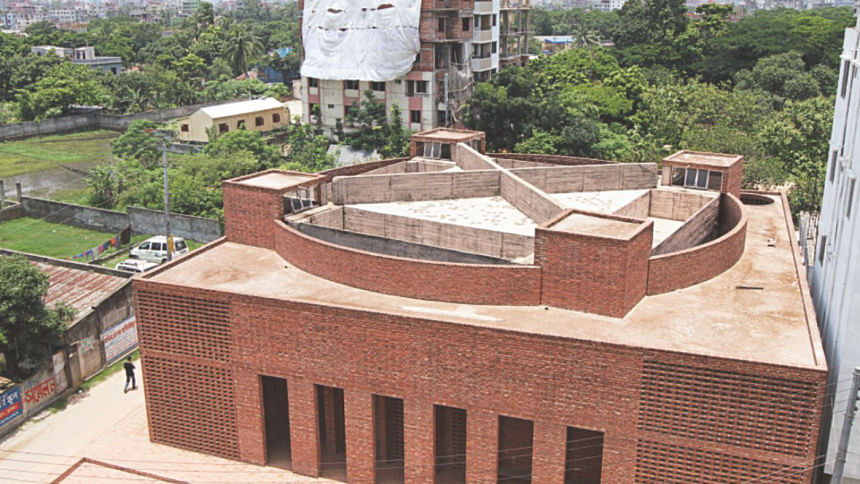

Truth be told, it was a sight to behold. Amidst the chaos of the half-constructed buildings, the dusty streets and the empty fields, the 75 by 75 feet structure in red stood apart, almost imposing itself over the buildings in the vicinity. And it wasn't really a tall structure. In fact, the first aspect about the Bait-ur-Rouf that hits you is the absence of a tall minaret or a dome, the classical symbols that one generally associates with a mosque.

As impressed as we were, our morale, for a split-second, hit a new low when the guardian of the prayer house told us that we would have reached here in just five minutes had we taken the newly-built road from Abdullahpur to Faidabad.

Sure enough, there probably were a few wrong turns taken during the journey, but as far as the decision to nominate the Bait-ur-Rouf mosque is concerned, no mistakes were made.

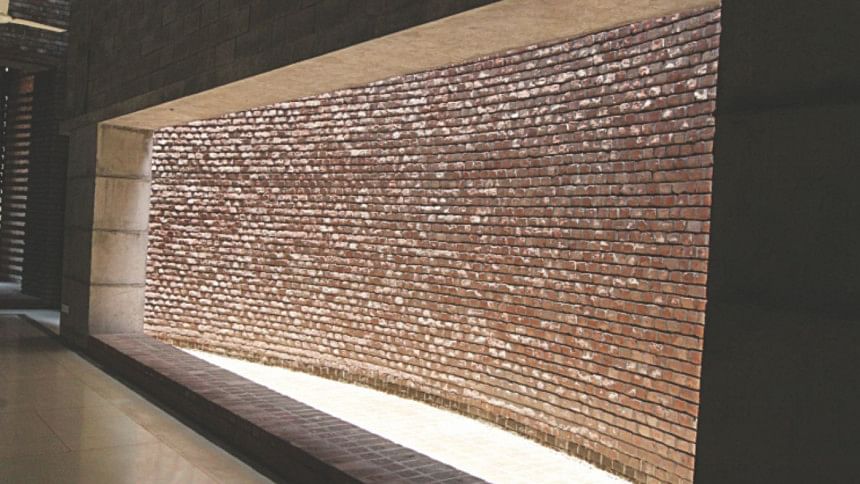

At first glance one notices the walls, designed intricately with bricks laid in a crisscross fashion so as to provide small gaps after every inch or so. And the result of it is obvious when you enter inside. At half-past 12 in the afternoon, the difference in the temperature inside the mosque was apparent.

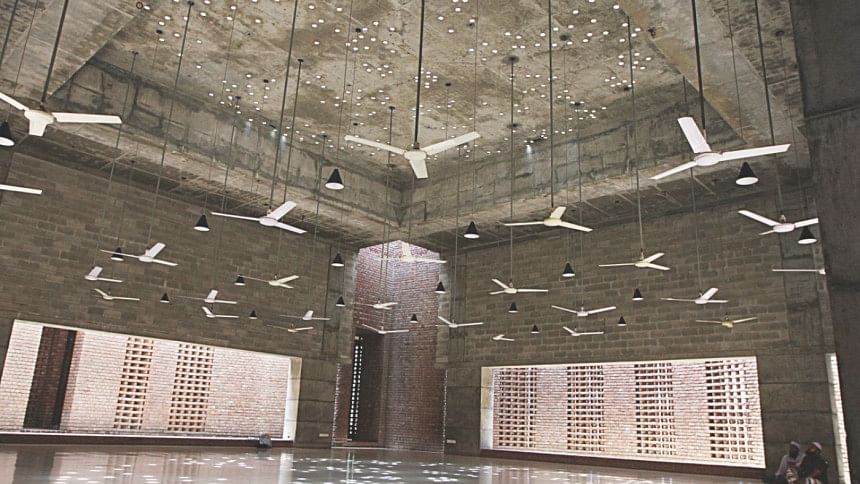

The fans were switched off and the mosque didn't have an air-conditioning system. The gaps in the walls though ensured that the cool breeze pass through. However, that wasn't even half as impressive as the rays of the sunlight that converged at the center of the prayer room, providing an extremely divine sensation.

These rays come through the various holes punched on the roof. Aside from providing a visual treat, it also ensures that there's always a draft of air at the top, thereby further lowering the overall temperature inside the Bait-ur-Rouf.

The unique aspects would have taken any passerby aback, however, to the designer of the structure, it was all about sticking to the roots.

“It's very much rooted in the history. If you look at mosque architecture historically, it generated from house form. It was a room where people would congregate to pray. Also not just prayer, during prophet's (pbuh) time various social, political issues and disputes were settled there.

“At that time it didn't have the elements that we associate with a mosque today. Whatever we associate with a mosque today, let's say the minarets and the domes, were introduced in different times for different reasons.

For instance, the dome came into being because that was the technical knowhow of that time to cover a large space. Over time, this has become a symbol we associate mosques with, even though we have various new technologies to span a large roof,” says Marina Tabassum.

“My focus was not to address the symbolic aspect but to concentrate on the spiritual ambiance and the act of praying. We come to a mosque to pray, to create a connection with the divine and that's what I wanted to highlight through my structure. I wanted to get rid of the extra fat and keep to the basics,” she adds.

Tabassum's idea was simple. She wanted to create a structure which had its roots in Bangladesh. “What I like to do in my practice generally is, root architecture to its place. To find its root, architecture needs to come from history, culture, climate etc. It's not just about the visual aesthetics. It's about combining all these elements of a place into a language of architecture. Not only is the historic reference of Islam important in this case but also the historic references of Bangladesh.”

“Our problem is that we have lost the rich glory of mosque building in Bangladesh. I think a mosque needs to be inspirational and spiritual enough to generate respect and create a divine feeling, otherwise it loses its purpose,” she adds.

The land for the mosque was donated to Tabassum by her grandmother. Like every other part of the city, Faidabad too grew with great pace and the locals required a place where they could congregate for prayer. That's when Tabassum's family, along with contributions from locals, and friends, decided to build the mosque.

The 11-katha project took her Tk 1 crore to complete. “That's quite small for a project of this scale,” she says.

This isn't the first time that Tabassum has been nominated for the Aga Khan Awards. She reached the finals once before for A5, the pavilion apartment in 2004. She seemed unmoved when asked if she expected to win this time. “There's still a long process to go. Who knows what happen?” she smiles.

Regardless of whether she wins the award, the fact that architects like Tabassum, who still prefer to treat structures as living beings rather than just commercial prospects, still exist in the country is in itself a boon. And it was this principle that led to the creation of the beautiful Bait-ur-Rouf.

Tabassum describes it best herself: “Architecture should be designed in such a manner that people can tell what place it belongs to. Quite often you see architecture that is so impersonal, that they could be everywhere yet belong to nowhere. That does not make any sense to me.”

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments