Dutch perspectives on early-modern Bengal

The riverine area of Bengal has held a significant position in Indian Ocean trade for centuries and has also given rise to different narratives about the region in European accounts. Bengal had long-established trading and diplomatic connections with China and South-East Asia. Rila Mukherjee pointed out that Chinese ceramic ware was found in the cities of Gaur and Punduah, and Chinese-style bricks and tiles were used in the urban houses of Gaur. Bengal's coins circulated in Mataram, Java, and there were mentions of merchants from Gaur in Majapahit, Java. Diplomatic exchanges between the Ilyas Shahi dynasty and the Ming dynasty occurred in the early fifteenth century.

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive in Bengal. Satgaon and Chittagong served as their two major ports. However, due to silting, Satgaon became obsolete, and Hooghly replaced it in 1579. The Portuguese continued to settle in the region, becoming detached from the Estado in Goa and Portugal. Some of them engaged in trade and missionary activities, while others turned to piracy. Together, they formed a kind of shadow empire in Bengal and settled in lesser-known ports such as the Sandwip Islands near Chittagong in Bangladesh.

The idea of branding Bengal in a stereotypical fashion was due to the association of sovereignty with geography. The act of 'claiming' a riverine region was an attempt to portray it as lawless and morally bankrupt. A political vacuum could then be established. This facilitated the imposition of Dutch authority or jurisdiction over the villages of that place.

In Jesuit Portuguese accounts, Mughal Bengal took on the image of a place filled with wonder, magic, and monsters. These accounts included tales of animal delegates sent from the king of Bengal to the Mughal emperors, behaving like humans. These stories contributed to a stereotypical portrayal of Bengal in Portuguese accounts.

With the dissolution of Portuguese settlements in Bengal, the Dutch East India Company arrived in 1603. The Dutch established their primary factory in Chinsurah and had factories in other regions such as Malda, Kasimbazaar, Dhaka, Pipli, Balasore, and Patna. They encountered the Portuguese, who were still residing and trading in Bengal, and spoke in a Portuguese creole language. Company officials soon began documenting their experiences in the riverine areas of Bengal. These accounts played a significant role in Dutch travel literature, giving the region a dual identity of prosperity and peril due to its rivers.

Jan Huygen van Linschoten, in his 1596 work "Itinerario," wrote about the flourishing land of Bengal, stating:

"The country is remarkably abundant and fertile, especially in rice... Numerous ships from various places come here to load themselves with this rice... and it is so affordable that if one were to describe it, it would sound incredible... There is an abundance of sugar and other commodities that highlight the region's wealth... Apart from rice, a substantial quantity of fine cotton textiles is produced, highly regarded not only within India and the entire Indian Orient but also in Portugal and other parts of the world."

However, with this tale of abundance, Linschoten also wrote about the wilderness and the danger posed by Portuguese pirates in the rivers of eastern Bengal. He wrote:

"The water (of the Ganges)… is so pristine and clear, that it seems to be like paradise… it has crocodiles, like the Nile in Egypt… The Portuguese have some of their trade and traffic there and their settlements in some of the places... but they have no permanence, nor any police or government as in (the rest of) India. They live by themselves like wild men and untamed horses, doing whatever they wish, being masters of themselves and not paying much attention to the legal system, and if they do, they often follow laws of Indian origin, and in this way, some of the Portuguese there sustain themselves."

Linschoten set the trend for describing Bengal in this manner. Other writers later picked up on this theme. The rivers and the unruly terrain became a standard stereotype reiterated in almost every account. In 1672, the Dutch geographer Olfert Dapper published his book, "Het rijk des grooten Mogols," where he presented similar ideas. Dapper highly praised the rivers of Bengal for their richness and prosperity:

"Those from Bengal, as Linschoten shows, claim that the Ganges originated in the earthly paradise, which is why they also consider its water sacred. It even attracts thousands of Banias and other Indian heathens who bathe in its waters… In the middle of the Ganges, there lie innumerable small and large islands which are very fertile, bearing wild fruit trees, pineapples, and all sorts of vegetables, while being crisscrossed with several canals or water channels (tributaries)."

However, these images were accompanied by the usual portrayal of danger and lawlessness in the region. Dapper noted that the islands in eastern Bengal were not under proper control and were left to be wild and desolate, infested by the Frankish pirates from Arakan. They were also teeming with "tigers that swam from one island to another, making it very dangerous to move in there." Dapper emphasized the tiger as a dangerous, exotic creature found in Bengal:

"It has… glistening eyes, sharp teeth, giant paws with bent claws, and long hairs on the lips: that are so poisonous that if one of these hairs gets into a man or even an animal, they succumb to the poison… nobody should, as forbidden by the Great Moguls, keep such hairs of a dead tiger for themselves, but on penalty of death (if violated), should send them to the court of the Great Mogul, where the King's physicians then made deadly poisonous pills from these hairs, that would be given secretly to anyone the King wished to kill."

Dapper had never traveled to India, but he consistently echoed the stereotypical description of Bengal as both prosperous and dangerous. During the last decades of the seventeenth century, Wouter Schouten visited the Company in Bengal. He published his experiences in a book in 1676 from Amsterdam. In it, he reported about the affluence of Bengal and its people but branded the region as perilous too. In his words,

"Bengalen or Bengala is a great and mighty land… Bengal is one of the most beautiful and productive countries in India. With the produce of this region, the people can feed not only themselves but also the inhabitants of other areas of India… We saw that Hooghly lay, great and beautiful, along the banks of the famous river, the Ganges. There were wide but unpaved streets, beautiful footpaths, and occasionally, here and there, some respectable buildings, wealthy warehouses, and houses built in the Bengali style. There were also shops filled with all kinds of commodities, especially beautiful silk cloth and other oriental textiles."

Conversely, Schouten infused elements of chaos and danger into his narrative by writing the following,

"With daybreak, we reached the village of Baranagore, where a large number of jentives, both men and women, disregarding the sharp chill, went shamelessly naked… to plunge themselves into the river. This was without consideration of the fact that crocodiles and alligators are found daily in these waters that are known to have frequently preyed on many human beings."

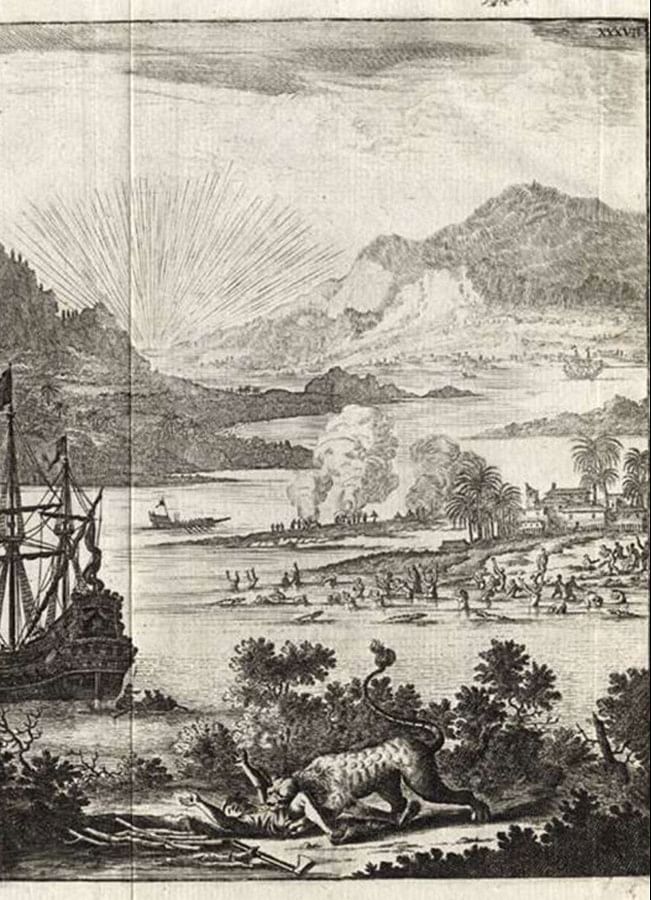

His text was accompanied by an illustration that conveyed the impression of Bengal being a prosperous and dangerous region. In this illustration, one can see different aspects of prosperity and peril huddled together in one frame. Scenes of cremation, a tiger attacking a woodcutter, and crocodiles in the water are juxtaposed against the flourishing commercial scene of ships and trade in the background. Schouten further wrote about the Portuguese pirates from Arakan who were feared by men with boats on the rivers of Bengal. Why were such accounts produced about the riverine geography of Bengal?

As Lauren Benton argues, the idea of branding Bengal in a stereotypical fashion was due to the association of sovereignty with geography. The act of 'claiming' a riverine region was an attempt to portray it as lawless and morally bankrupt. A political vacuum could then be established. This facilitated the imposition of Dutch authority or jurisdiction over the villages of that place. The Dutch not only traded in Bengal in textiles, sugar, saltpeter, and opium but also acquired zamindari rights over the three villages of Chinsurah, Baranagar, and Bazaar Mirzapur. The simultaneous promise of affluence in the region made it a lucrative area to administer. The Company officials who held jurisdiction frequently interacted with the Mughal administrators in Bengal. Before the Company officials came to be formally recognized as zamindars in the eighteenth century, there were cases of individual conflicts between the Mughals and the Dutch. In response to these conflicts, the Dutch accounts dismissed Mughal rule in Bengal as improper and corrupt governance. Pieter van Dam, the advocate of the Dutch East India Company, was assigned the task of compiling the Company's history. In his work titled Beschryvinge der Oost-Indische compagnie, Van Dam wrote,

"The Mohammedans, who, as they say, rule the land and government, are of a large number and are mighty and greedy. The regents have a very small piece of land, in comparison to that of their king, who is a great and powerful monarch… these arrogant regents and their slavish subjects, are false, flattering, and exhibit no moral virtues… one should try to please them as much as possible; otherwise, they are capable of causing much damage and harm to us… the general populace here (in Bengal) is poor and slavish, and repressed harshly by this Moorish government."

Similar observations on the inefficiency of the Mughal government appeared in the administrative reports. While writing about the diwan of Bengal, Rai Balchand, Jacob Verburg, the Dutch director, described him as a "shrewd money-grabber." Hendrik Adriaan van Reede, the Dutch commissioner in 1687 wrote,

"The government in this land (Bengal) curtails the fruits that can be reaped out of it (for the Company)… Bengal is administered by Shaista Khan… the predominant nature of the prince enjoying the highest authority called Naboob is extremely greedy; as a consequence of which he is neither the happiest nor righteous in his administration… The regents (meaning administrators) are extravagantly grand, selfish, and conspicuously pompous with their lifestyles, (the standards of) which are often more than their power and income. They are drawn to tyranny and extortion, not only from their unregulated squandering behind women, servants, horses, tents, camels, and elephants but also for having more resources to maintain their households and their (political) favorites in their courts."

Such descriptions of the Mughal governance in Bengal in the seventeenth century, coupled with the narrative about the riverine landscape, helped the Dutch East India Company establish its claims over the region. After the decline of the Mughals, the Nizamat of Bengal permitted the Dutch East India Company to trade and administer their zamindari in Bengal. The victory of the English East India Company at the Battle of Plassey tightened English control over Bengal, which made the Dutch alarmed. A Dutch-English battle was fought called the Battle of Bedara at sea and on land. The Dutch East India Company was defeated in the battle, and the English curtailed their trading rights in Bengal. After two brief periods of English intervention, the Dutch possession in Bengal was relinquished to the English East India Company in 1825.

Byapti Sur is an Assistant Professor of History at the Thapar School of Liberal Arts and Sciences in Patiala, India.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments